How the trains came to Santa Cruz – Part 2 (April 19, 2012)

By October of 1875, Santa Cruz had its first railroad (see part 1). The Santa Cruz & Felton Railroad did not, however, satisfy the needs of most city and county residents. It ran from Santa Cruz to Felton, mostly over the same route traveled today by the Roaring Camp and Santa Cruz Railroad (aka “The Beach Train”).

By October of 1875, Santa Cruz had its first railroad (see part 1). The Santa Cruz & Felton Railroad did not, however, satisfy the needs of most city and county residents. It ran from Santa Cruz to Felton, mostly over the same route traveled today by the Roaring Camp and Santa Cruz Railroad (aka “The Beach Train”).It was primarily a freight line, at first used mostly by the lumber interests that had financed its construction. As soon as new sidings could be built, Felton lime manufacturers, California Powder Works and the San Lorenzo Paper Mill also started using it. A passenger connection to the outside world, however, had to wait most of a year, and came from a completely different direction.

Although Frederick Hihn’s earlier investment in the Felton rail route had not turned out well, his next railroad venture did better. After several years of frustration in trying to obtain construction funding through the county, Hihn formed a railroad company with "The Sugar King", Claus Spreckels. Spreckels, like Hihn, came to California as an immigrant from Germany, and became wealthy in the sugar business in San Francisco. Other partners included Ben Porter (the tanner) and Titus Hale, who leased the Aptos wharf from Rafael Castro. These entrepreneurs formed a private company called the Santa Cruz Railroad (SCR), and proposed a route from the Southern Pacific terminal in Pajaro, through Aptos and Capitola, and on to Santa Cruz.

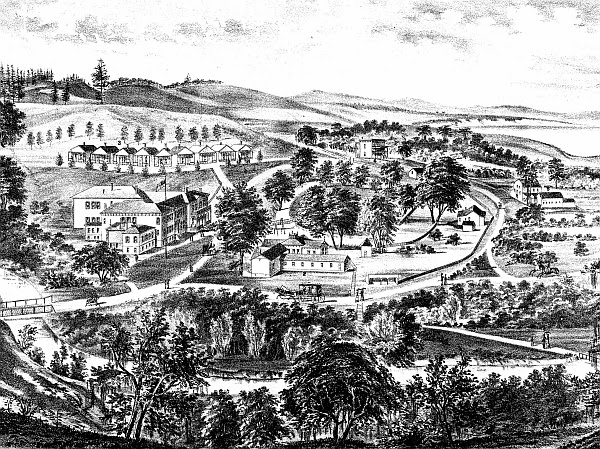

Up to now, there hasn’t been much mention here of Aptos history. Some of the old settlement on Rafael Castro’s Rancho Aptos remained from Alta California days. By 1860, there was a general store and a grist mill in the village, and Porter’s tannery was just to the west. The development pace began to pick up in the 1860s as timber harvesting and lumber milling became the county’s largest industry. The first sawmill and first bridge over Aptos Creek were built in 1860. Hihn built a sawmill on Valencia Creek in 1870.

Then, in 1874, Spreckels bought over 2,000 acres of land from Castro, stretching from today’s Rio del Mar beach to the redwoods. As one of the principal investors in the SCR, he knew that the railroad would multiply the value of his land, and he got busy preparing for it. In 1875, he opened the expansive Aptos Hotel, including detached cottages and a riding stable, just in time to greet the first passengers on his new railroad.

Naturally enough, the railroad’s owners made sure it ran through or very near to their properties. But past Aptos to the east, there was a bit of a quandary. To avoid major elevation changes, the line stayed near the coast until it reached the flat expanses of the Pajaro Valley. From there, it might seem natural to angle directly across the valley to cross the Pajaro River near the Southern Pacific terminal. That would, however, have brought the line near Watsonville and Hihn was not inclined to do that town any favors. Its leaders had opposed the use of county funds to finance the railroad’s construction. Although their stated sentiments were loftier, I’m sure they were thinking; “Hey, Watsonville already has a rail connection right across the river – why should we pay taxes to build an extension to Santa Cruz?” Hihn and partners were understandably unhappy with Watsonville, and perhaps planned to deliberately bypass the town out of spite.

When the Watsonville leaders saw the proposed route staying close to the coast, however, they filed a lawsuit to force the SCR to bring it inland closer to town. Hihn and the others had probably, by this time, seen enough of lawsuits and delays. They agreed to re-route the line, and Watsonville dropped the lawsuit.

You can still see this abrupt change of plans in the rail line today. From La Selva Beach, the tracks run roughly parallel to the coastline, then make an abrupt left turn toward Watsonville just before reaching Beach Street. The railroad dispute was possibly the beginning of the Santa Cruz-Watsonville rivalry that continues today.

The SCR’s decision to begin construction in the middle meant that, for more than two years, the railroad did not connect to either of the two largest towns in the county. The first track was laid in December of 1873, and by May of 1875 the line was complete between Aptos and the east bank of the San Lorenzo River in Santa Cruz. While the trestle was under construction, passengers bound for downtown Santa Cruz presumably hired a carriage to take them over the new covered bridge at Soquel Avenue - the nearest bridge at the time.

Work continued in both directions and, on May 13, 1876, the first train from Pajaro crossed the new San Lorenzo River trestle. My two main sources disagree on which engine pulled the first train into Santa Cruz. McCaleb claims it was the Jupiter , a brand-new 22-ton steam-powered locomotive that was actually the 3rd or 4th locomotive purchased by the railroad.

It seems unlikely that the Jupiter was put in service that early, but we’ll go with that story anyway because, by a fortuitous chain of events following a colorful later career, the Jupiter ended up at the Smithsonian Museum in Washington, D.C. The engine and the story of its Santa Cruz past are now in a permanent exhibit, and the Santa Cruz Railroad story is included in an online educational series.

Once across the trestle, the tracks followed an odd course. The line at first followed today’s route along the future Beach Street, but did not directly connect to the Santa Cruz & Felton line at the railroad wharf (even though both were narrow-gauge lines). Instead, the two sets of rails crossed at a right angle, with the SCR line continuing under a rebuilt and raised Bay Street bridge (replacing the old bridge built in 1849 by Elihu Anthony). From there, the line turned north along the future Chestnut Street to a depot on Cherry Street (today’s Union St.). It’s unclear whether, at first, there was a switch allowing the SCR trains either to use the railroad wharf or to connect to the SC&F tracks.

One more project addressed that problem, as well as one other concern about the SC&F. The Santa Cruz leaders were not thrilled with the idea of heavy freight trains running down the middle of Pacific Avenue, so part of the agreement with SC&F was a stipulation that freight cars be unhooked from the engine north of downtown and pulled by horse teams the rest of the way to the wharf. No one was happy with that arrangement, and plans were soon made to bypass downtown.

Obstructing that plan was one large obstacle – Mission Hill. The solution was to dig a 900-foot-long tunnel through the hill. Work on the tunnel began in 1876 and was finished before the end of the year. The two railroads were connected and an SC&F depot built at the south end of the tunnel.

One other rail system began operation in Santa Cruz during the same few years – streetcars. Our first public transit system, and maybe some later railroad history, will be the subjects of How the Trains Came to Santa Cruz – Part 3.

Additional online source:

Hamman, Rick. 140 Years of Railroading in Santa Cruz County. (SCPL)